What is it like to have your period in a developing country?

Today is World Water Day.

Access to clean water is a fundamental of life. But water goes beyond what we drink.

Even in countries where adequate drinking water is available, access to water for washing, and clean facilities to wash in, is limited. This has a particularly negative impact on women and girls experiencing their period.

For many women and adolescent girls where IWDA works in Fiji, Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea, having your period already means being excluded from many aspects of daily life. It can mean bullying, shame and abuse. It can mean using whatever materials you have at your disposal to create makeshift pads, because quality products are not affordable or available. It can mean burning your sanitary items for fear of putting them in the bin, where they could be seen.

Poor access to sanitation facilities further compounds this.

As a region, the Pacific varies greatly when it comes to sanitation facilities, women’s and adolescent girls’ rights and access to education around sexual health and reproductive rights. But across the board, women are still facing huge barriers to living with safety, freedom and dignity during different life stages.

The Last Taboo

Up until recently, there has been limited research on menstrual hygiene management in the Pacific. In 2016, the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) funded research to explore the challenges facing women during their periods, how women deal with them, and hear from women what their recommendations are to better be supported to effective manage menstruation. This information will be used to inform programming responses

The Last Taboo: Research on menstrual hygiene management in the Pacific: Solomon Islands, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea was conducted by the Burnet Institute, WaterAid and IWDA.

The research is based on findings focus group discussions, interviews and observation of the facilities available to women. So what did it find?

There’s a huge urban rural divide

It’s important to note that Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands are each unique, with their own distinct cultural and ethnic makeup, geographic spread and levels of gender inequality. But differences don’t just exist between countries. There’s also a huge divide based on where you live in these countries.

In Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands, most of the population lives a semi-subsistence lifestyle in rural areas, where accessed to improved sanitation like hygienic and private toilet facilities is only available to roughly 15% of the population.

Living rurally doesn’t just affect sanitation facilities – it can mean the difference between access to quality sanitary products and being forced to use uncomfortable, often makeshift substitutions. Girls in rural Solomon Islands, for example, have the most limited access to high quality and affordable sanitary products. These inferior products can result in rashes, discomfort and leakage, which can cause pain and further perpetuate the cycle of shame.

Disposal and hygiene

When women and girls are unable to access or afford sanitary products, many resort to rags, cloths, newspaper or layering underwear. This can stop girls from fully engaging in school; according to one student, “For me, I go to school [while menstruating] but only for half days…during break time I go back home.”

Women, particularly those in informal work, also find disposal and personal hygiene and issue in the workplace. In Solomon Islands, one woman reported going to the sea to wash herself, which can be a safety risk. Going out alone to a remote area can expose women to physical, sexual or emotional violence, especially they only feel comfortable to do so after dark because of the stigma.

Professional disposal services are available in some areas of urban Fiji and Papua New Guinea, but more than likely, sanitary items, professional or makeshift, are wrapped up and taken home, left around toilets, put in bins on the street, or even burned. Others may avoid changing them all together, which can lead to rashes and other avoidable health complications.

Menstruation is rarely taught in schools – and girls with disabilities often miss out entirely

In Fiji, girls are taught about periods and how to manage them at school in sex-segregated classes. While it’s not perfect, and there are still gaps around cycles, girls are generally supported with how to manage their first period.

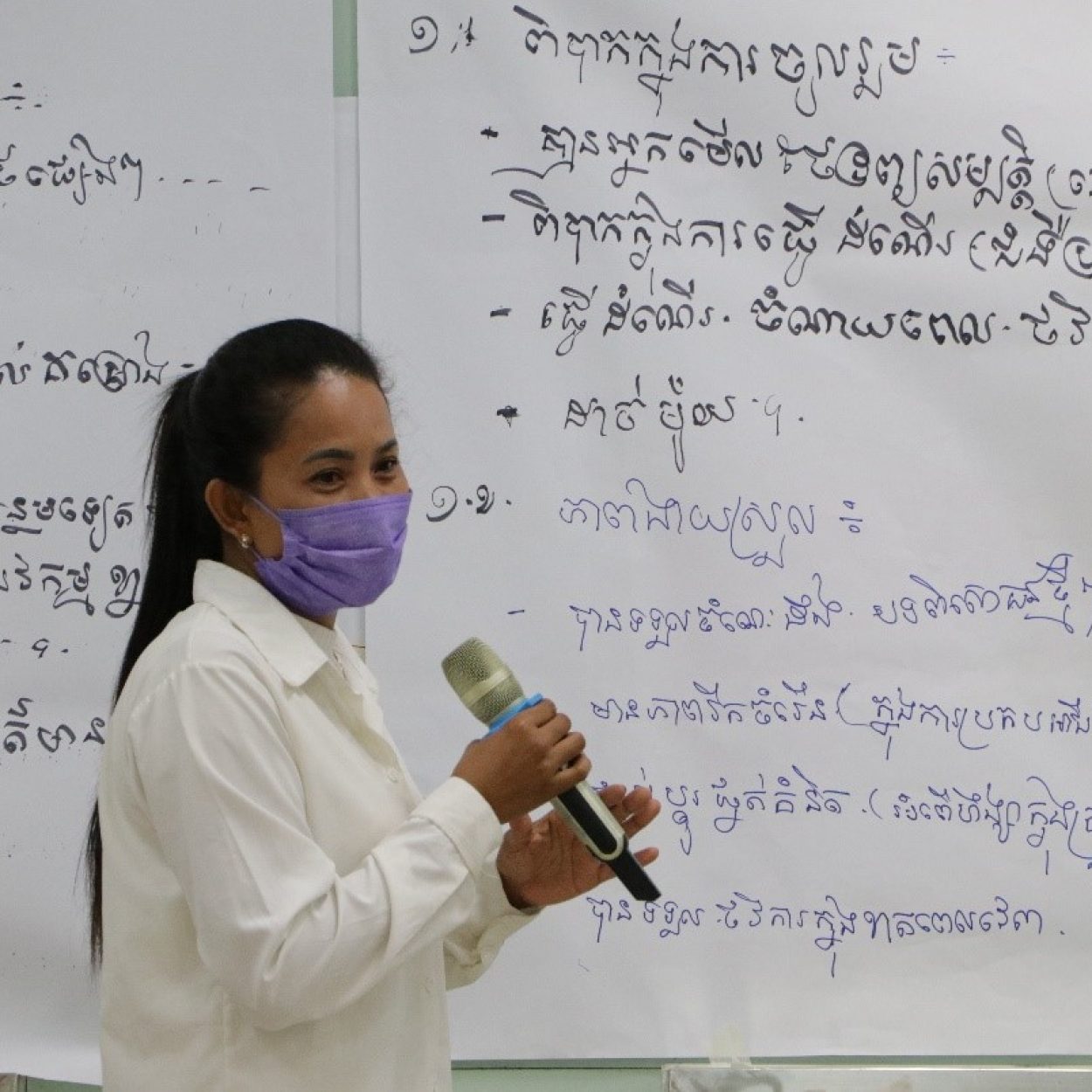

In contrast, Papua New Guinea and Solomon Islands are only given the very basics about puberty – with boys in the classroom, periods aren’t discussed for fear of embarrassing the girls. This leaves girls unprepared for their first period, leaving them scared, ashamed and unprepared. Teachers have the knowledge, but according to one teacher in Papua Guinea, often need training in how to educate their students around menstruation.

“One of the difficulties the teachers face – they have the knowledge to teach in class, but they need training in how to teach it.”

This is problematic not only in terms of girls’ mental wellbeing when their first get their period, but around knowledge of fertility when they choose to become sexually active.

Across all three countries, women and girls with disabilities frequently miss out on education and support around their periods; despite being more likely to experience sexual harassment, violence, and deprivation of basic human rights.

Periods are ‘dirty and unclean’

We all know periods are a normal function – but bullying around girls’ periods was prevalent across the region, particularly in Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. In Solomon Islands, periods are still taboo even amongst siblings – girls must take care to not let their brothers know they are menstruating. According to one anonymous health worker in Solomon Islands, it’s something that should remain a secret.

“When we have our period our brothers must not see it. If they see you have period and stain on the clothes you will give them money to show respect for disrespect because they see this.”

Women are often forced to live apart or stay indoors, not handle food and stay away from gardens and churches because they are considered tainted and unclean. As hugely important social activities, this leaves women isolated from their communities, and can reduce their income if forced to stay away from their normal income generating activities.

What next?

The strength of the research gathered for Last Taboo is that it’s rooted in the experiences of women and girls in the Pacific and captures their voice and experience. By engaging with women and girls in Fiji, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea, the research builds a clear and complex picture of women’s experiences with menstruation.

Despite the vast differences between each country, the research highlights a need for action in each region. Its three recommendations are:

- Strengthening education around menstruation and puberty and challenging discriminatory taboos

- Improving availability, affordability and access to sanitary items, particularly in schools and workplaces

- Improving the sanitation and hygiene of washing facilities and give women a safe way to change and dispose of soiled products

IWDA, through our work as technical consultants with Live and Learn International, work with Pacific communities to improve access and knowledge around water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), with particular focus on how these elements affect women. We firmly believe the voices of women and girls in the Pacific must be incorporated in any initiatives that impact them, and will continue to take a rights-based approach that involves the input and expertise of women in the Pacific.