The women left behind by Cambodia’s pandemic response

For just a moment, let us take you back to the start of 2020.

Back to when we were just starting to come to terms with the novel coronavirus and what it would mean for (what we then thought would be) the next few months.

At the time, a lot was said about COVID-19 and the effects it was having globally. That is was indiscriminate and somehow a great equalizer when it came to how it would affect people across the world.

More than two years on from the first recorded case of COVID-19 and we now know all too well that while the virus might have infected people indiscriminately, its effects were far from equally felt.

Like with all crises, this pandemic has been felt the hardest by those already marginalised. In 2020, global extreme poverty rates rose for the first time in over 20 years with about 100 million additional people now living in poverty as a result of the pandemic.

Over and over again, we are seeing how this pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities, with the harshest economic and social impacts falling on those who simply cannot afford them.

In Cambodia, things are sadly no different.

The Cost of Lockdowns

As COVID-19 case numbers rose globally at the start of 2020, Cambodian authorities quickly passed a new State of Emergency Law that gave them the power to impose severe restrictions on citizen movement, assembly and freedom of speech. Sold as a way to help limit the spread of COVID-19, the draconian law has served to further restrict civil society and limit space for dissent in the country.

Following its adoption, curfews and domestic travel restrictions were quickly implemented, tourism visas were suspended and land borders closed. At a surface level, these decisions turned Cambodia into a success story. By January 2021, the country had recorded no COVID-related deaths, with only 463 cases being reported – 86% of which were from overseas cases.

Yet for many Cambodians, this victory felt hollow as they were left to face a second, growing crisis.

While the government’s approach might have helped stave off the virus for most of 2020, these severe restrictions were particularly damaging to the country’s trade and tourism industries – the very same industries that many vulnerable and marginalised Cambodians rely on for their livelihoods.

With many small and local businesses closing, mass cancellations of orders within the all-important garment and footwear industries and the tourism sector essentially coming to a halt, hundreds of thousands of low-wage workers have been laid-off or suspended since the start of the pandemic. As a result, poverty levels have doubled in Cambodia, with few low-income families having the level of savings needed to sustain themselves for months without work.

The February 2021 Outbreak

A string of community outbreaks broke Cambodia’s lucky streak last year when, in February, case numbers rose from a few hundred to tens of thousands, with the total number of COVID-19 cases now having surpassed 120,000 in 2022. At different points in time, parts of major cities in the country were designated as ‘red zones’, with provincial authorities having the power to enforce localised movement restrictions in high-risk areas. For those living within these zones, at times that has meant living under full lockdown conditions for up to 35 days last year, with residents prohibited from leaving their homes – even to purchase food.

While the government has introduced various emergency assistance programs in the form of one-time cash transfers and relief packages to low-income households, their delivery has been selective and haphazard at best. There has been a general lack of transparency around how at-risk households are identified for transfers while the food aid provided to households in red zones have been sorely inadequate. The income support provided has been similarly lacking, with the government only covering 50% of garment workers’ wages following the closure of their factories without accompanying subsidies on their bills.

The Law on Preventive Measures Against the Spread of COVID-19 and other Severe and Dangerous Contagious Diseases

In the midst of all this, civil society organisations are also having to deal with the impacts of the government’s draconian legal reforms such as the State of Emergency Law and the Law on Preventive Measures against the Spread of COVID-19 and other Severe and Dangerous Contagious Diseases. The new regulations mean people could be fined or face prison sentences of up to 20 years for lockdown breaches. It also gives the government the power to indefinitely ban gatherings or demonstrations. With vague and ill-defined offences included within its remit, the law has basically turned into a way for the government to silence critical or dissenting voices in Cambodia.

This builds on the increasingly restrictive environment the government has created over the years, using the guise of COVID-19 to increase their control over the country. For civil society organisations and women human rights defenders, the laws have greatly limited their capacity to speak out against the government’s actions, with many fearing arrest if they were to publicly criticise their COVID-19 response or attempt to form a protest of any sort. It has also made it harder for organisations like United Sisterhood Alliance – IWDA’s partner in the region – to provide essential assistance to women workers at a time when they need it the most.

COVID-19’s Impacts on Sex Workers

The latest round of restrictions has also served to further marginalise an already vulnerable group within Cambodia. In response to COVID clusters within the nightlife industry, authorities ordered the temporary closure of entertainment venues such as KTVs (karaoke bars that also double as brothels), beer gardens and bars, amongst many others. Sex workers and entertainment workers are finding it increasingly difficult to earn a living as a result of this loss of income, the closing of their workplaces and increasing targeting of freelance sex workers by security guards – all while the cost of living in Cambodia continues to increase.

While government aid has flowed to workers within the tourism industry, entertainment workers have largely been left to fend for themselves.

As Polet Pech, Managing Director of the Phnom Penh-based Women’s Network for Unity (WNU) – a member organisation of United Sisterhood Alliance – says, the pandemic and increasing restrictions it has brought about has left many sex workers facing increased levels of social exclusion, stigma, discrimination and hardship. Only 8% of sex workers have the official “ID Poor” cards needed to access financial support and free healthcare, she explained, with many having to resort to ways of getting by that are further disadvantaging them when it comes to accessing support. Many, for example, have had to sell their phones for much-needed cash, preventing them from registering for emergency food packages provided by the government.

“We lost our income since the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. We can’t afford to pay the room rental fee and we don’t have enough food and household debt [is] increasing. Also, we couldn’t meet even to talk about reproductive health problems,” an independent sex worker speaking to United Sisterhood Alliance

The continued closure of KTVs, along with venues like massage parlours and beer houses, has also meant that sex workers and entertainment workers are now putting themselves in increasingly dangerous positions to make a living. With entire families depending on their income to survive, many have had to take their work to the street and other dangerous available jobs. There, sex workers face increased risk of violence from clients and are still routinely arrested by police for allegedly causing public disorder before being sent to the Prey Speu Detention Center, where they are imprisoned without criminal charges.

In a six-month period, WNU was contacted about 84 cases of sex workers being intimidated by police officers, of being evicted by landlords and of having to work without pay.

According to a June 2020 study by WNU, 93% of women sex workers have faced significant impacts on their livelihoods as a result, with 45% of women interviewed saying they had no work to fall back on. By the end of 2021, the situation had only gotten worse as many of them also faced increased debt as a result of the extended lack of work.

Despite being some of the worst affected by this pandemic, sex workers have continuously been scapegoated for community transmissions. Instead of providing them with the essential support they need to make it through this pandemic, the Cambodian government has fostered an environment where sex workers have had to shoulder most of the blame for these continued outbreaks – all while casinos, which have been at the centre of outbreaks in Cambodia, have continued to thrive.

United Sisterhood Alliance: a lifeline in difficult times

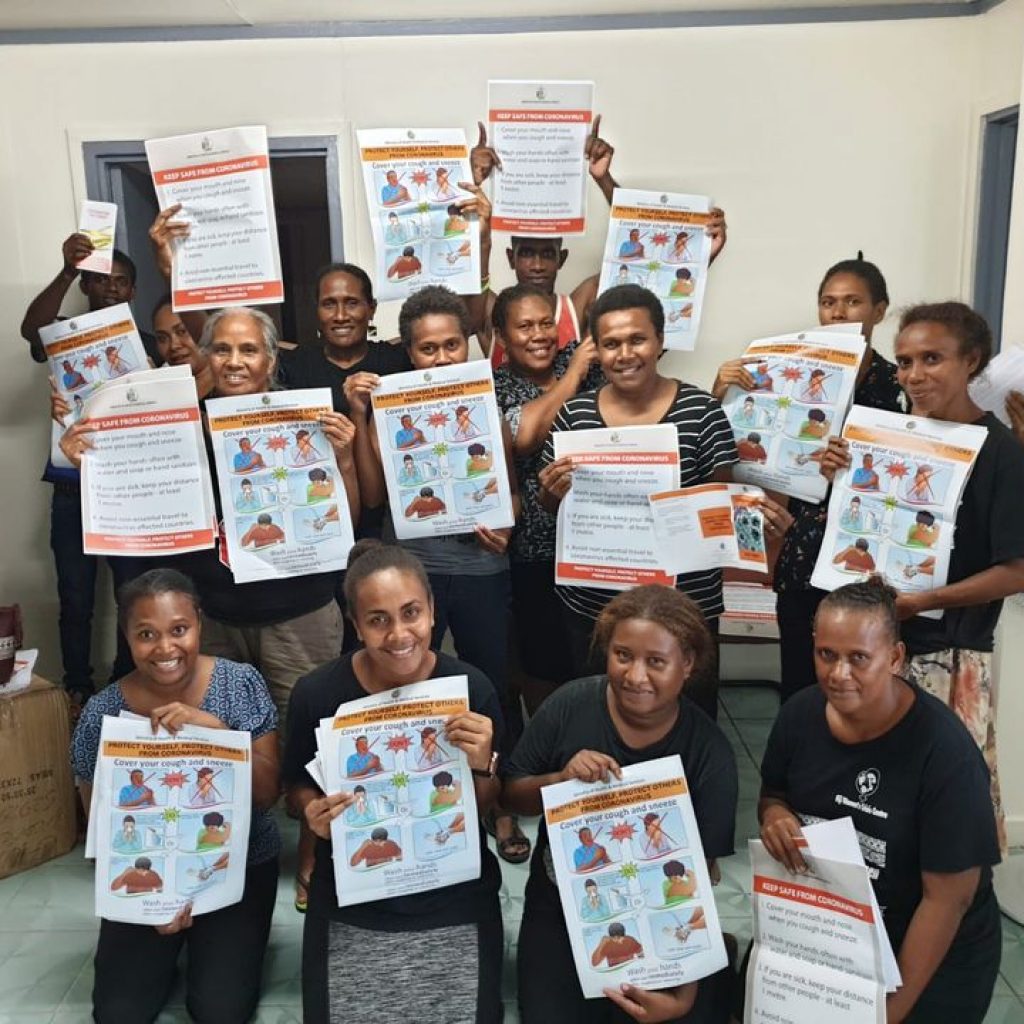

IWDA partner United Sisterhood Alliance has been working hard over the past two years to fill this void left by the government. Where possible, they have provided emergency assistance and support to sex workers and entertainment workers who are ineligible for government assistance. This has included providing them with essential supplies like rice, dry foods, face masks and hand soap. They have also offered cash support to families who do not have the capacity to store food but were left out of the government’s one-time cash transfer.

Member organisations have provided emergency support to 550 marginalised women affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly women workers experiencing income loss, including small-scale farmers, garment workers, sex workers, entertainment workers and students.

United Sisterhood has also created important spaces for women to be heard. They have organised and convened a number of dialogues for women workers, farmers and university students to discuss the impact COVID-19 has had on their lives.

In a testament to the strength and importance of feminist coalitions across regions, United Sisterhood Alliance has also extended its advocacy work to the current situation in Myanmar. They organised a solidarity talk on the recent military coup in Myanmar, developing advocacy messages that they shared with Women’s League of Burma – one of IWDA’s partners in Myanmar – and have been raising funds to help support civil disobedience movements against the junta.

In the face of a government that is leaving behind some of the most vulnerable within its population, United Sisterhood Alliance is providing much needed assistance to garment, entertainment and sex workers. It is also increasing the space and opportunity for their voices to be heard, engaging in essential advocacy work that can set the foundations for more equitable and fairer crisis responses in the future.

United Sisterhood Alliance is funded by the Foundation for a Just Society through the Movements and Voice for Equality (MOVE) program in partnership with IWDA.